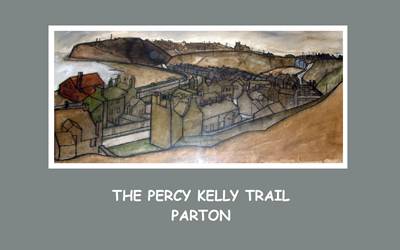

Parton Trail

Parton is a hidden village. It crouches between the shore, the railway and steep cliffs. It can’t be seen from any of the roads into Whitehaven and has been overshadowed by that town over centuries.

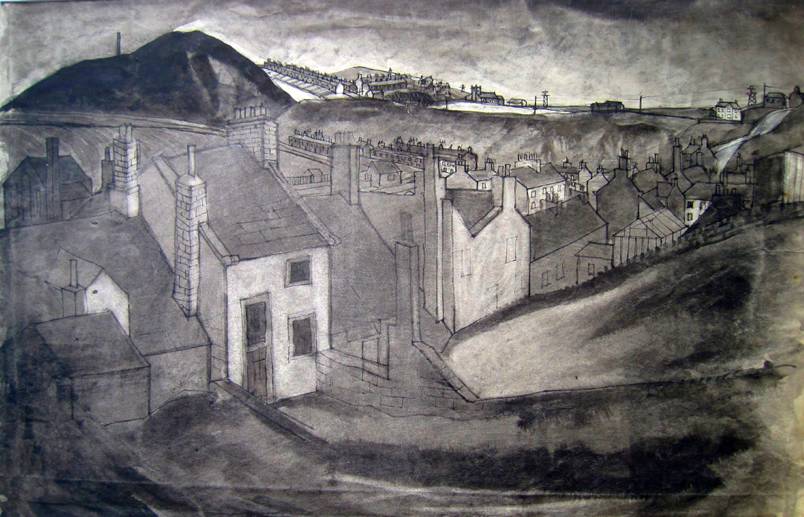

Percy Kelly was painting and drawing here from the fifties when he returned from war service and was reluctantly directed back into working for the Royal Mail and given more responsibility. This left him little time for art so he became depressed and eventually resigned taking over a sub post office and general store at Great Broughton leaving his wife Audrey to do most of the work while he escaped to paint. This was a time of huge development in his work and we see here the difference between the early watercolours and the growing confidence and bold, steady lines of sixties work.

By the mid sixties Kelly was focusing on Parton, Moresby and Whitehaven because he had attracted the interest of Sir Nicholas Sekers (and his family) an industrialist and founder of Rosehill Theatre who lived in nearby Moresby. Kelly suddenly found himself part of the social scene. His yellow MG was often seen in the area. Sir Nicolas’ daughter Christine and her French husband Jean Beaudrand loaned him an outhouse at Roseneath to use as a studio.

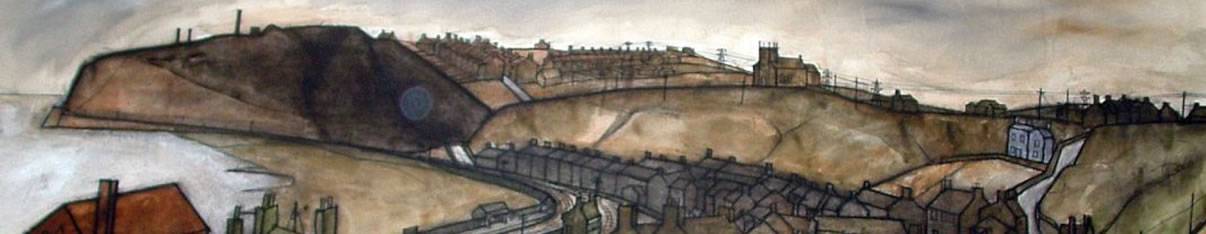

It is easy to see why Kelly would find Parton attractive. The curve of the railway, the juxtaposition of the higgledy piggledy houses and the sinister church and Hall silhouetted on the skyline were suited to his style, palate and mood.

Parton has had mixed fortunes over the years. It prospered for decades on its glassworks, tannery and brewery followed by the coal mine and iron foundries - particularly Lowca engineering founded in 1800 which made the first locomotive for the new railway line from Carlisle to Maryport. It prospered even more when the railway was extended south. Its decline was gradual. First to go was the harbour which was not as sheltered as Whitehaven and was destroyed in a storm in 1795. Later the pits closed one by one and by the depression in the thirties Parton was no more than a forgotten and neglected dormitory village. In a rare interview for the BBC for the opening of an exhibition of some of his Parton drawings in 1964, Kelly said there was an urgency in drawing and painting the village because it was disappearing as he worked. In fact the council were demolishing a lot of the old houses which were unfit for habitation and relocating people to the new housing estate on top of the hill. The people of Parton have proved themselves resilient to withstand all these changes.